The Institute at 10 – The Multiplier Effect: Climate and Conflict in the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa

25/03/2025

In 2024, on the occasion of the 10th Anniversary of the establishment of the European Institute of Peace, the Institute commissioned a series of articles about our work, interviewing staff members, senior advisors, and people who have worked with us in the past decade on conflict prevention and resolution in different areas of the world.

How best to communicate our work is not obvious. Discretion is often an essential ingredient to what we do, for example around dialogue and engagement with parties to conflict and their supporters. But we cannot afford not to communicate in an increasingly crowded media and public affairs environment, one in which political and public recognition is too low regarding the value and practical benefits of the work that we and our partners undertake. “What you are doing is great – why aren’t you telling more people about it?” is a typical reaction from partners that want to increase their support for us. Sharing these stories about the Institute’s work is of the ways in which we are responding to these requests.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, of the 20 countries most affected by climate change, the majority are at war. Not only is climate change a driver of instability and conflict, but armed conflict is often a cause of environmental degradation. During the first two years of the conflict in Ukraine, carbon dioxide emissions directly related to the war stood at 175 million tonnes – more than the yearly output of the Netherlands. In Gaza, the UN Environment Programme estimates that over 100,000 cubic metres of sewage and wastewater are currently being dumped daily onto land or into the Mediterranean Sea as a result of infrastructure damage. In 2019, Europe’s military carbon footprint alone was estimated at around 24.8 million tCO2e, equivalent to the CO2 emissions of about 14 million average cars. War is waste.

Recognising both the relationship between armed conflict and climate change, in early 2019, the European Institute of Peace established a dedicated unit, the Climate and Environmental Peacemaking Programme. The Programme responds to the security and conflict risks posed by environmental challenges by engaging parties to conflict, opening new avenues for dialogue, building trust and relationships, and providing policy advice on climate and environment. It creates a space for greater civil society input by also being the bridge between populations and decision-makers, and shifting the consciousness of those in power.

The Institute has implemented bespoke projects which engage directly with the environmental aspects of conflict in the Liptako-Gourma region of West Africa, in Yemen, and Somalia. This has enabled the Institute to connect mediators to technical expertise on climate science, identifying and socialising peace dividends related to climate action, such as stability, economic growth and development. It advocates for the necessity of putting climate front and centre when it comes to peacemaking. Seeking out other partners who are equally passionate about tackling the nexus between climate and security is also a priority.

Since 2022 the European Institute of Peace has been a core member of the ‘Weathering Risk Peace Pillar’, which seeks to address climate security risks through peacemaking and peacebuilding. Together, these initiatives argue for a response to climate change that goes beyond the work of scientists, to involve others with direct experience studying and responding to climate’s relationship to conflict.

Engaging Climate Experts in Peacemaking

One of those initiatives was a complex survey that produced surprising results. The Institute’s Pathways for Reconciliation project asked nearly 16,000 Yemenis to voice their needs and priorities. This is the largest exercise of its kind ever undertaken in Yemen. The poll found that the environment ranked among the top three concerns in eight out of nine of Yemen’s governates. In four governates it was the number one concern, ranking even higher than the cessation of fighting.

In hindsight, this was not surprising. Yemen currently ranks 171 out of 182 for climate vulnerability. Over 70% of the country’s population rely directly or indirectly on agriculture. In recent years, Yemen has suffered drought, flooding, disease outbreaks, locust infestations and rising sea levels. In 2023, natural disasters forced close to 320,000 people from their homes. An estimated 19.5 million people depend on some form of humanitarian assistance at present, and many are having to resort to unsustainable well-drilling, cash crops and uncontrolled tree felling for fuel to secure their basic needs.

Capitalising on the insights gained from the Pathways for Reconciliation programme, the Institute launched a follow up initiative – the Environmental Pathways for Reconciliation.

Crowd-Sourcing Solutions to Climate and Conflict

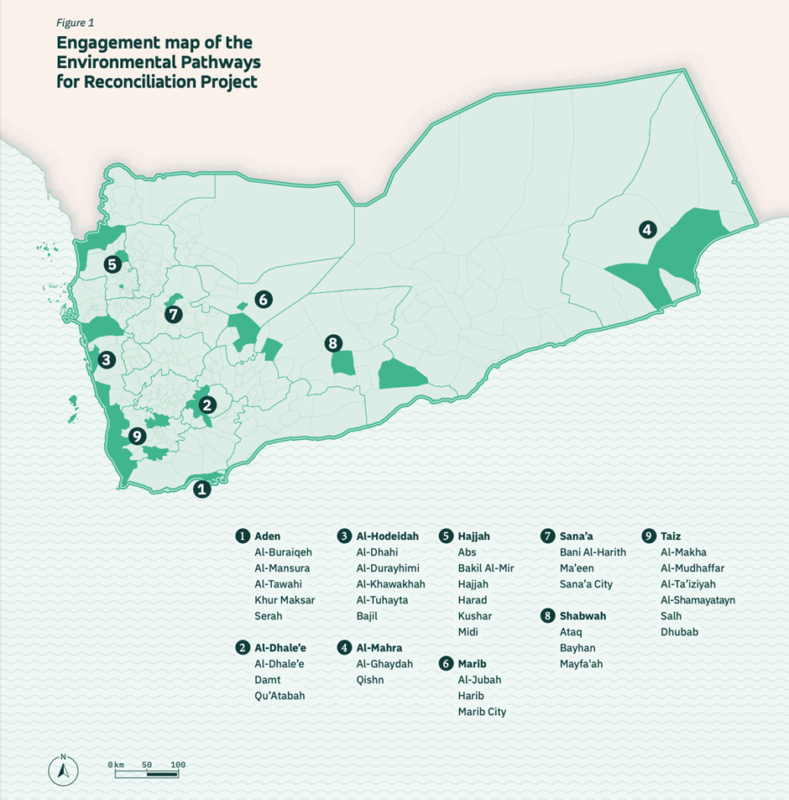

Yemeni journalist Suaad Abdullah supported a series of local consultations and dialogues on the interrelations between environmental challenges and the conflict. “When I joined the Environmental Peacemaking Programme I was afraid – how would I manage to gather all the stakeholders and different parties in one room?” she said. Travelling to sites across the country, Suaad Abdullah and her team engaged over 2,400 people across the nine governorates of Aden, Taiz, Marib, Al-Mahra, Al-Hodeidah, Shabwah, Sana’a, Al-Dhale’e, and Hajjah in a mixture of surveys, focus groups, key informant interviews, and community dialogues. The goal of Environmental Pathways for Reconciliation was to better understand and contextualise local perceptions of the challenges surrounding climate and conflict — and to identify opportunities and potential solutions.

The results of the consultation confirmed how central environmental concerns were to any potential resolution of the war. 92% of respondents perceived a reduction in the availability of and access to natural resources in the past years. Critically, more than half said that they had experienced tensions or conflicts in their areas relating to environmental issues. 85% of those consulted considered it essential to address climate change in the short-term, with 60% insisting that environmental considerations be integrated into any conflict resolution in Yemen. Issues raised ranged from poor sanitation and access to clean water in IDP camps and informal settlements, desertification, flooding and droughts, and the decimation of local fishing.

While the initiative focused on Yemen’s general population, it was critical to not exclude decision-makers and local power holders in the dialogues. Suaad Abdullah says that it wasn’t always easy to convince local leaders to participate, but that the results when they did were often surprising and encouraging. She adds that even if local populations were acutely aware of how climate change was driving the conflict, in some cases it wasn’t always easy to get local elites to make the connection. But often she didn’t need to – communities themselves were ready and able to get the message across to local government and take advantage of rare opportunities for frank and open exchange with decision-makers. She recalls one instance in a community dialogue in Ma’rib –

“We had a real mix in the group, local sheikhs, academics, farmers. Some were confused and started arguing, asking what the connection was between climate and conflict. I wanted to reply to them, but before I could, a local farmer stood up and addressed the group. “If you don’t know about the link between the environment and peace,” he said, “it is a disaster, and you are driving conflict in this governorate.” The farmer went on to explain that years ago he was a rich man, earning 100,000 USD from his land cultivating and selling fruits and vegetables. With desertification in recent years his earnings were reduced to 20,000 USD. “What of someone who was already poor, what will they do, to whom will they turn?” he asked. At that moment I saw that the group understood, and even started to give their own similar examples – local conflicts over access to wells, all sorts of things. I understood then the power of these meetings.”

Local NGOs, tribal mediators, traditional elders and minorities were all able to take advantage of the shared space to connect and share resources, knowledge and contacts to help stimulate efforts to find solutions to shared environmental problems.

In Yemen, societal fragmentation and state collapse mean that environmental governance is virtually non-existent. “When it comes to preparations and capacity to manage the environment at the local and national level, for sure we are at zero,” Suaad says. In that context, instead of demanding for improved environmental governance as a precursor to sustainable peace, Environmental Pathways for Reconciliation works from the ground up, engaging the people most directly affected by the conflict and the environmental crises. After consultations across the country to understand the issues from a local perspective, the project continues its engagements at the governance level, to map solutions, connect these ideas to funding, and implement them on the ground.

It’s still early in the process, and there’s much work to be done, but already ideas are starting to surface: the use of clean fuel for cooking, green belts to fight desertification, local committees to mediate climate-related disputes, early warning systems, and the use of solar energy as an alternative to diesel and gas. The energy and passion is there, the challenge is only to direct and coordinate the huge potential of the collective intelligence of the Yemeni people. When organisations like the Institute are able to hold the space for local actors to come together and dialogue in a structured way, the possibilities are endless.

“In Al Mahrah, our commitment to protecting the environment, our people, and the sea knows no bounds. We stand ready to make sacrifices and take decisive action to safeguard our precious natural resources. But we recognize that we cannot do it alone. United as men and women committed to the betterment and safeguarding of our region, we stand ready to face the challenges ahead and forge a brighter future for Al Mahrah and its inhabitants.”

Radhwan Mohammed Saeed, a local fisherman from Al-Mahrah and participant in the Environmental Pathways for Reconciliation community dialogues.

Credits: Nazeh Mohammed, EIP 2023

Crossing the Gulf: Getting the Message to Power

The consultation in Yemen showed that while local communities may be experts on issues in their own regions, they don’t always possess the bigger picture at the broader level. Pushing for climate analysis when it comes to conflict resolution also means engaging institutions and governments.

Across the Gulf of Aden from Yemen, in Somalia, the Institute has been able to achieve notable progress in bringing climate change to the centre of the debate around peacemaking.

As in Yemen, Somalia grapples with the devastating impact of drought, flooding, desertification, biodiversity loss, sea level rises and extreme temperatures. These issues have wreaked havoc on Somali society and added further layers of complexity to local conflicts, giving rise to resource scarcity and competition, displacement and migration, livelihood disruption and humanitarian crises. In many cases these issues have made communities increasingly susceptible to recruitment by armed groups such as Al-Shabaab, clan militias, Ahlu Sunna Wa Al-Jama’a, and others.

Before the Institute began directly engaging with officials in Mogadishu, local government did not treat environmental issues as important conflict drivers. Three years ago, the programme responsible for climate issues was limited to a small desk in the prime minister’s office. Lack of coordination and at times competition between Somalia’s federal states meant that comprehensive approaches to climate were often complicated and stalled.

Engaging with governments on environmental matters

The process took time. Sensitising ministers about how to better engage on climate and conflict isn’t just about dealing with a lack of will or capacity. We are all collectively learning how to understand and tackle climate concerns today, and in many cases governments are also learning to adapt and require inputs not only from civil society, but also knowledge from other governments and international bodies.

With the support of the Federal Ministry of Environment and Climate Change of Somalia, the Institute facilitated three Cross-Ministerial Workshops. The workshops demonstrated the value of convening multiple governmental actors to discuss technical environmental matters, such as climate finance and climate security, as an entry point for dialogue and trust-building that can lead to greater cooperation in a context of political and institutional disagreement.

The direct engagement, coordination, and policy support that the Institute provided to federal and state-level actors, coupled with their active involvement in environmental peacemaking activities, have significantly shaped their understanding, capacity, and attitude towards addressing environmental and climate security risks. New policies implemented by different parts of the government now recognise the importance addressing these risks in collaboration with other actors who share similar mandates, notably the reviewed Nationally Determined Contributions to the Paris Climate Agreement.

Stepping up to the Challenge

Ensuring climate change is at the heart of peacemaking also requires financial support. Climate finance to help fragile and conflict-affected states mitigate the threat is still lagging far behind what it needs to be. In the cases of Somalia and Yemen, two of the most vulnerable countries, climate finance averaged only 2 USD per capita over the period 2014-2021.The situation is improving slowly, with global climate financing estimated at 1.3 trillion USD in 2023 – double that of 2019. But that’s still only 1% of GDP dedicated to a challenge that threatens humanity with civilisational collapse.

By 2031 it’s estimated that we’ll need to be putting at least 10 trillion USD into climate adaptation if we are to get anywhere close to staving off the worst impacts of ecological collapse. Conflict is often the driver of change, and the solutions arising from the frontlines of Yemen, Somalia and other countries facing the double crisis of climate change and armed conflict may yet lead the way for us all. But we need to be there to support them.

Somalia has for years been plagued by tensions and competition between Mogadishu and the regional government of Puntland to the North. Despite bitter conflict in the Galkayo Mudug region between the autonomous state of Puntland and neighbouring Galmudug state, (part of federal Somalia), severe drought in 2016 presented a rare opportunity for the two parties to cooperate. In response to the drought, authorities allowed herders from Galmudug state to bring livestock to graze deep inside Puntland territory.

Opportunities like that are rare. In this case, one was seized. It’s become a useful example of how efforts to confront climate change will now form part of any effort at peace building.