The Institute at 10 – Coming of Age in an Age of Change: A Decade of the European Institute of Peace

20/03/2025

In 2024, on the occasion of the 10th Anniversary of the establishment of the European Institute of Peace, the Institute commissioned a series of articles about our work, interviewing staff members, senior advisors, and people who have worked with us in the past decade on conflict prevention and resolution in different areas of the world.

How best to communicate our work is not obvious. Discretion is often an essential ingredient to what we do, for example around dialogue and engagement with parties to conflict and their supporters. But we cannot afford not to communicate in an increasingly crowded media and public affairs environment, one in which political and public recognition is too low regarding the value and practical benefits of the work that we and our partners undertake. “What you are doing is great – why aren’t you telling more people about it?” is a typical reaction from partners that want to increase their support for us. Sharing these stories about the Institute’s work is of the ways in which we are responding to these requests.

You could be forgiven for missing the offices of the European Institute of Peace, tucked beside the Basque mission, on a quiet side street in the European district of Brussels. Only a stone’s throw from the enormous headquarters of the European Commission’s Directorate-General for International Partnerships, the organization’s modest 19th century stone building lacks the usual rows of flags and cold glass of the Commission’s office just down the hill. It cuts quite a different image. In fact, it’s not even part of the European Union. And that is sort of the point.

Officially, the European Institute of Peace is a ‘foundation’ under Belgian law. It maintains strong connections to grassroots actors on the ground, like an NGO. But it also has access to high level government circles, like an international organization. Uniquely, the Institute moves between worlds, operating in a space that includes both diplomats and social movements, armed rebels and humanitarians, scientists and artists, economists and activists.

An Idea Whose Time Had Come

In 2009 the late Martti Ahtisaari, former Finnish president and Nobel Peace Prize winner, called for the establishment of a ‘European Institute of Peace’. Foreign Ministers Alexander Stubb of Finland and Carl Bildt of Sweden took the idea a step further in 2010, submitting an informal discussion paper to Catherine Ashton, at the time High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. The paper captured a sentiment that traditional diplomacy, while by no means obsolete, was becoming increasingly limited in its capacity to mediate conflicts and seek out sustainable peace in today’s world. The fall of the Berlin wall may have brought the world closer together, but the globalisation of neoliberal norms which went with it also had a profound – and often disruptive – impact on how power would soon be distributed, both between and within states.

What Europe needed was a body closely connected to the EU and European states, but independent, and not bound by the bureaucratic and political constraints of Brussels. This new kind of organization would be able to engage with a broader range of state and non-state actors, both European and otherwise, through a greater variety of formal and informal means. It would bridge the gap between high-level politics and newer, less centralized and more complex ways that power moved in the world of conflict prevention and resolution.

After four years of consultations, studies and workshops — and with support from European diplomats, international organisations and conflict experts growing — on 12 May 2014 the vision finally became a reality and the European Institute of Peace was officially launched by the foreign ministers of its nine founding board members: Belgium, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. The Institute was to be a centre of excellence in the understanding and praxis of conflict prevention and resolution, designing and engaging actively in peace dialogues, training mediators, and providing support to peacemaking efforts around the world. Not only would it assist conflicting parties outside Europe to find common ground, it would also serve as a bridge between Europe and the world, to share experiences, listen and learn.

It wouldn’t be easy. Around the time of the European Institute of Peace’s inauguration, Boko Haram kidnapped 100 schoolgirls in Nigeria, deadly clashes with ISIS rocked in Iraq, and pro-Russian separatists declared the independence of Donetsk and Luhansk in eastern Ukraine.

Different Vibes for Different Tribes

In a way, the somewhat austere, neoclassical stone exterior of the Institute offices is an apt metaphor for the way the organisation presents itself to official Brussels. It’s formal when necessary and versed in the diplomatic etiquette needed to ensure messages from the ground are heard at the top. That’s what the media might imagine conflict mediators do most of the time. But the Institute does much more than that: one of its unique strengths is the ability to interact with all kinds of actors on the ground, from marginalised communities to armed groups, from citizens’ movements to heads of government.

With the average age of staff a youthful 32, the European Institute of Peace’s office feels more like a technology start-up than a diplomatic organization. An entrepreneurial spirit has been part of the culture since the beginning. Staff were encouraged to experiment, be imaginative, and take risks in the pursuit of peace. Growing from a handful of Brussels-based staff, the Institute now has a permanent team of approximately 50 full-time personnel. They in turn support a global network of over 100 experts, advisors and local partners working in more than 20 conflict-affected regions over the past ten years.

Geopolitics headed in a worrisome direction during that first decade. The writing may have been already on the wall in 2014: that we were entering a period of significant upheaval, more challenging than we could have imagined.

Brave New World

Standing at his desk trying to somehow make sense of the mosaic of coloured blocks that is his weekly meeting agenda, Michael Keating lets out a heavy sigh. It’s not just his dismay at his unending list of meetings with donors, diplomats, researchers, journalists, and civil society groups trying to navigate conflicts everywhere from Kyiv to Kinshasa. That’s nothing new for a man whose professional trajectory has included everything from finance to documentary film production to UN deployments: Afghanistan, Malawi, Israel, Palestine, New York, Geneva, Pakistan and Somalia, where he was Special Representative of the Secretary-General. He joined the Institute as Executive Director in late 2018.

Rather, his frustration is more at what he perceives to be uncertain political will to invest in peace and the shrinking space for organisations like the European Institute of Peace to operate. He can struggle to contain his exasperation when he looks out at what he sees as a world turning its back on dialogue and comprehensive approaches to conflict resolution in favour of hard security, defence, physical borders, inadequate humanitarian interventions, zero-sum politics and quick wins.

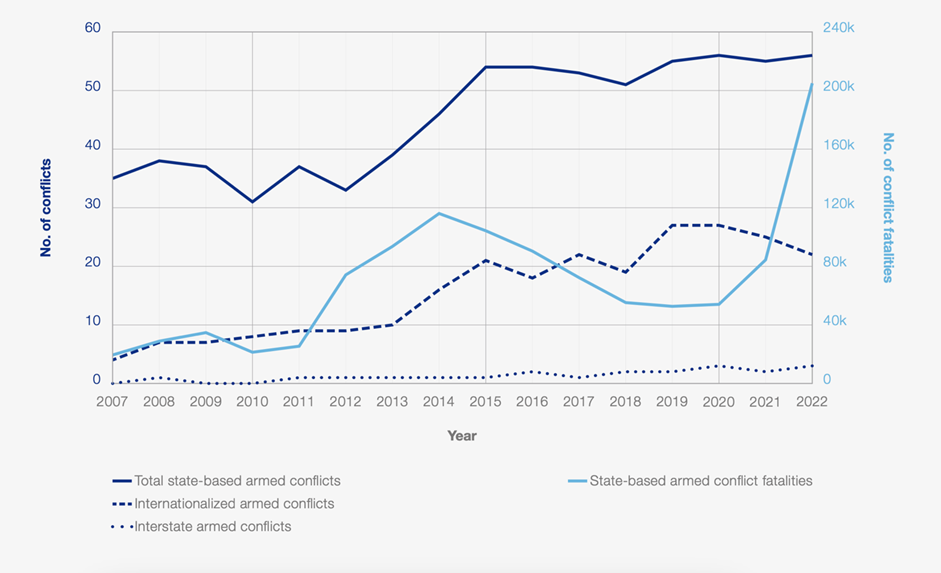

Active conflicts are at their highest levels in decades, and after a slow decline in the last 20 years, conflict-related deaths are dramatically increasing, not least as a result of the wars in Ukraine, the Middle East and Sudan. At the same time, the authority of the intergovernmental institutions set up to prevent and resolve wars has significantly diminished.

We might even look back with envy at the world when populism, social-media fuelled polarisation, AI, cyber-attacks, misinformation, disinformation and deep-fakes were not the pervasive problems they are today. A world less fragmented by armed, non-state groups, and where a full-scale land invasion of Europe’s eastern borders was still relatively unthinkable. Where there was respect for rules-based norms of international relations. Observers now speak of a ‘geopolitical recession’, where the “playbook for international relations, diplomacy and political good manners is being re-written”. For Europe, these challenges have increasingly played out at home.

Investing in Peace in Times of Conflict

As the world shuns multifaceted dialogue in favour of realpolitik and defence spending, the political will to invest in sustainable peace, and to support organisations like the European Institute of Peace, diminishes. Governments pour billions into defence spending but are disinclined to invest a fraction of that money for far less risky business of authentic dialogue and mediation. The reasons vary but often come down to “it’s not a priority” and “it’s just not realistic”. And when they do fund such work, they often want to see tangible or even immediate results, and conflict resolution can be a very slow process. How can you establish trust and build real relationships with partners on the ground when you may need to pull the plug on dialogue processes before they reach a sustainable conclusion?

The Institute’s level of unrestricted funding has gone from 46% of its total in 2015 to just 15% today. This reflects success in crafting and projects but limits its scope to take initiative, respond to crises and catalyse larger efforts to prevent and resolve violent conflict. Constantly running programmes on a short-term, hand to mouth, project by project basis is simply not sustainable, for either the Institute and its peer organisations, for conflict affected populations, and for donors that demand sustainable results.

The temptation is to market activities not on the grounds of resolving grievances, but rather because they could serve a particular political end, such as controlling immigration, counter terrorism, accessing resources or securing international shipping lanes. These objectives are politically compelling but when they displace the goal of advancing and securing sustainable peace as an end in itself, the result is an approach that is ineffective at achieving its intended political aims – and that is morally questionable in the way it instrumentalises human relations. There is a need to make the case for reversing this relationship, that politics can serve peacemaking, not the other way around.

The European Institute of Peace is uniquely placed to step in and provide practical support to a variety of actors to prevent and resolve violent conflict – and in particular to support the European Union to fulfil its core mission to promote the rule of law and lasting peace in an increasingly geopolitical and contested environment. To do so, it needs predictable and long-term support to do what it was designed to do and to fulfill the founding vision.

In conflict resolution, the odds are rarely in your favour. But sometimes it’s when the odds are stacked against you that pushing for peace is most important. The risks of doing nothing are simply too great, and relationships built and maintained at the darkest moments repeatedly prove their value when circumstances create the possibility, gradually or suddenly, of political progress. What is unrealistic is not so much investing adequately and consistently in the painstaking business of peacemaking. Rather, it is to expect political breakthroughs or peaceful and secure outcomes if we are not prepared to make that investment.

[ssba-buttons]